How does the diagnosis of dementia proceed?

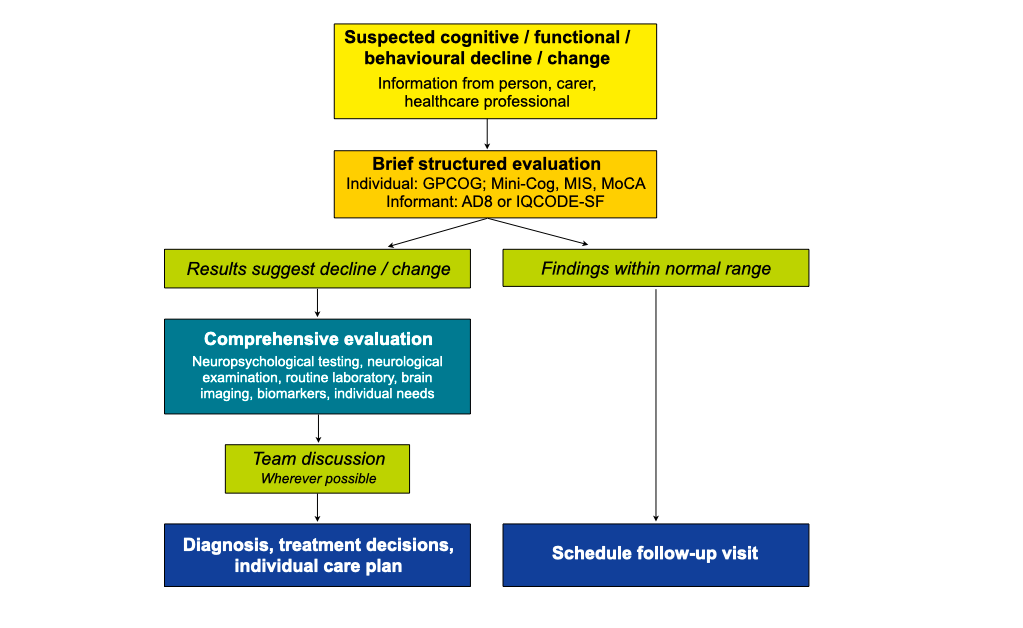

The diagnostic evaluation is usually triggered off by complaints of a person about cognitive decline and / or observations of family or friends regarding changes in abilities and / or behaviour. A brief structured evaluation should be followed by a comprehensive examination. The brief evaluation usually takes place on the primary care level (provided by general physicians, trained nurses). The comprehensive evaluation is performed on the secondary care level (provided by specialists, e. g. in memory clinics).

The process of dementia diagnosis

Which information needs to be obtained?

To establish the diagnosis of dementia and distinguish it from normal ageing and other health problems that may resemble dementia (depression, delirium) information must be obtained on:

- medical history;

- medications taken;

- cognitive abilities;

- performance on basic and complex activities of daily living;

- behaviour – particularly mood, initiative and interpersonal relationships;

For the assessment of cognition, daily activities, and behaviour valid and reliable instruments and tools are available. Acquiring this information is not exclusively a physician’s task – other professions such as nurses, social workers, occupational therapists and physical therapists can provide valuable input.

To identify the underlying cause(s), distinguish between causes, detect potentially reversible causes, and reveal comorbid conditions and risk factors, examinations are needed regarding:

- the physical status of the person (internistic and neurological examination, routine laboratory examinations);

- structural changes of the brain (computed tomography – CT – or magnetic resonance imaging – MRI – scan)

Additional investigations may be applied in questionable cases and in individuals with early onset, family history, unusual presentation, or rapid progression, including:

- biomarkers in the cerebrospinal fluid;

- positron emission tomography (showing metabolic activity or localisation of abnormal proteins);

- genetic testing.

To establish an individual care plan, additional information is needed on:

- individual needs, preferences, risks, resources and available support.

Brief structured evaluation

For the brief structured examination a number of tests and rating scales are available. Examples are the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), Mini-Cognitive Assessment (Mini-Cog), Memory Impairment Screen (MIS), General Practitioner Screening Test for Dementia (GPCOG) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Of note, the person with suspected dementia must consent to being examined and family members or friends being interviewed. If the person is unable to provide consent, a legal representative must agree with the examination.

Brief instruments for the evaluation of cognitive abilities

| Instrument | Time needed [min] | Contents |

| MMSE | 10-15 | Tests of orientation, memory, naming, praxis, language, visuospatial function |

| Mini-Cog | ≤ 5 | 3-item memory test and clock-drawing test |

| MIS | ≤ 5 | 4-item memory test |

| GPCOG | ≤ 10 | 6-item test plus informant interview |

| MoCA | ≤ 10 | Tests of memory, attention, language, naming, abstraction, orientation, executive and visuospatial function |

The person must consent to be examined

The examination of the person with suspected dementia must be complemented by an interview with carers about the performance on activities of daily living. Brief instruments recommended for this are the AD8 Dementia Screening Interview (AD8) and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale (IADL).

Brief instruments for the evaluation of activities of daily living

| Instrument | Time needed [min] | Contents |

| AD8 | 5 | 8 questions about everyday activities, judgment, use of tools, forgetfulness and orientation |

| IADL | 10-15 | Managing telephone calls, using public transportation, shopping, preparing food, housekeeping, doing laundry, taking medications, handling finances |

The brief structured examination should conclude with informing the person and their family about the findings, the need for further assessments and/or follow-up, if applicable.

Comprehensive evaluation

The aim is to reveal the cause(s) for the cognitive and functional decline and/or behavioural change. The individual may be examined by several specialists (neuropsychologist, neurologist, psychiatrist and neuroradiologist). The comprehensive evaluation usually encompasses neuropsychological testing, neurological examination, routine laboratory assessments, and CT (computed tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance) brain imaging. In selected cases, biomarkers in the cerebrospinal fluid are analysed. The comprehensive evaluation should also include an assessment of individual needs, risks and resources.

Neuropsychological testing

There is a large selection of tests that can be applied for the assessment of various cognitive domains according to the reported or suspected domains of impairment (learning, short-term and long-term memory, attention, reasoning and problem solving, spoken and written language, visuo-perceptual abilities, basic and complex motor skills, as well as the ability to understand emotional expressions and social interactions (social cognition)).

Neurological examination

It includes the general physical and neurological status of the person (e.g. for signs of Parkinson’s disease or stroke) and a check of medications used (e.g. for drugs that worsen cognitive abilities, or substance abuse).

Routine laboratory assessments

These include complete blood count, kidney and liver function tests, vitamin and hormone levels (especially B12, folic acid, thyroid hormone) to detect infectious and metabolic diseases.

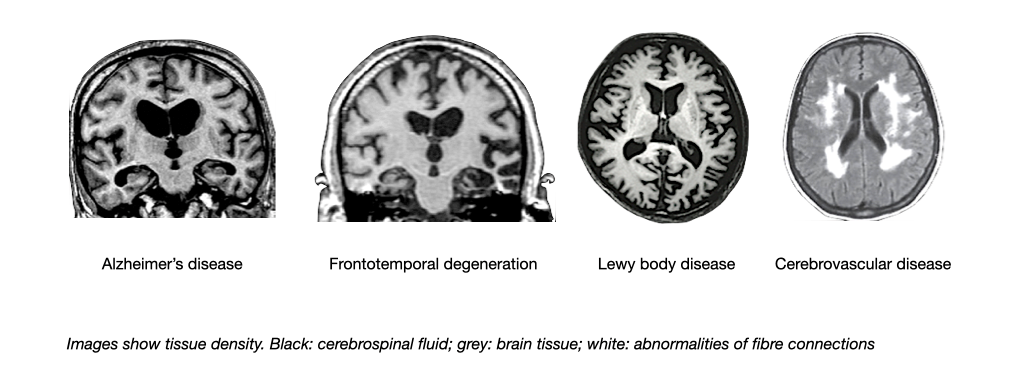

Brain imaging

Structural brain imaging including computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) help to detect brain tumors, infarcts, bleedings and other structural changes of the brain. They also reveal regions of the brain that are smaller than normal due to a loss of nerve cells (atrophy). The pattern of brain shrinkage and lesions differs between major causes of dementia (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease; frontotemporal degeneration; Lewy body dementia; vascular dementia).

MRI: Patterns of brain shrinkage and lesions in major causes of dementia

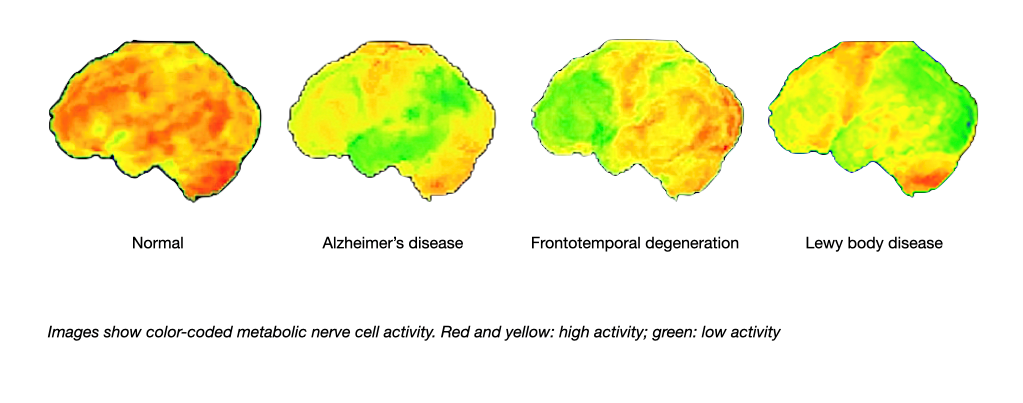

Magnetic resonance imaging also can demonstrate damage of fiber tracks due to small vessel disease. A technology called positron emission tomography (PET) can be used to visualise the activity of nerve cells and thereby the localisation of brain diseases.

PET: Patterns of nerve cell activity in major causes of dementia

Recently, positron emission tomography has also been employed to assess the deposition of the two proteins beta amyloid and tau in the brain. Amyloid and tau imaging has the potential of identifying the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease many years before first symptoms occur.

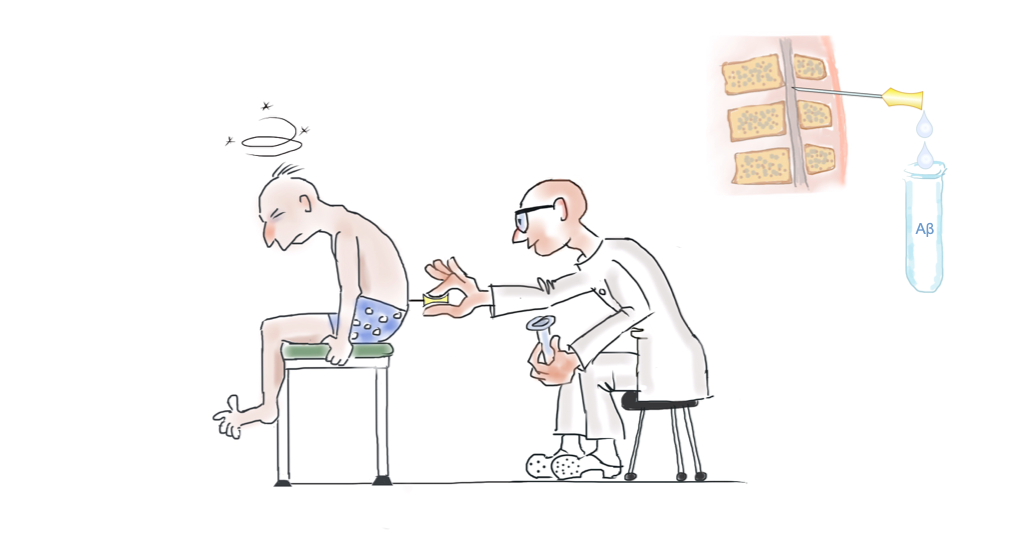

Biomarkers in the cerebrospinal fluid

The concentration of the proteins beta amyloid and tau can be measured in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) which is obtained through lumbar puncture. Alzheimer’s disease has a typical „signature“ of these biomarkers (lower than normal beta amyloid, higher than normal tau). The CSF biomarkers can be used to distinguish between causes of dementia and to estimate the likelihood of developing dementia in people who already have minor degrees of cognitive impairment. The use of CSF biomarkers in people who have no symptoms is not recommended because the predictive value regarding the future development of cognitive impairment or dementia is low.

Genetic testing

Two forms of genetic testing need to be distinguished. Diagnostic testing is performed in individuals who already have symptoms to confirm the diagnosis. Predictive testing applies to individuals who have no symptoms but are at risk (for example, evidence of a strong family history of dementia) to determine their likelihood of developing cognitive decline or dementia. Predictive testing must follow strict guidelines.

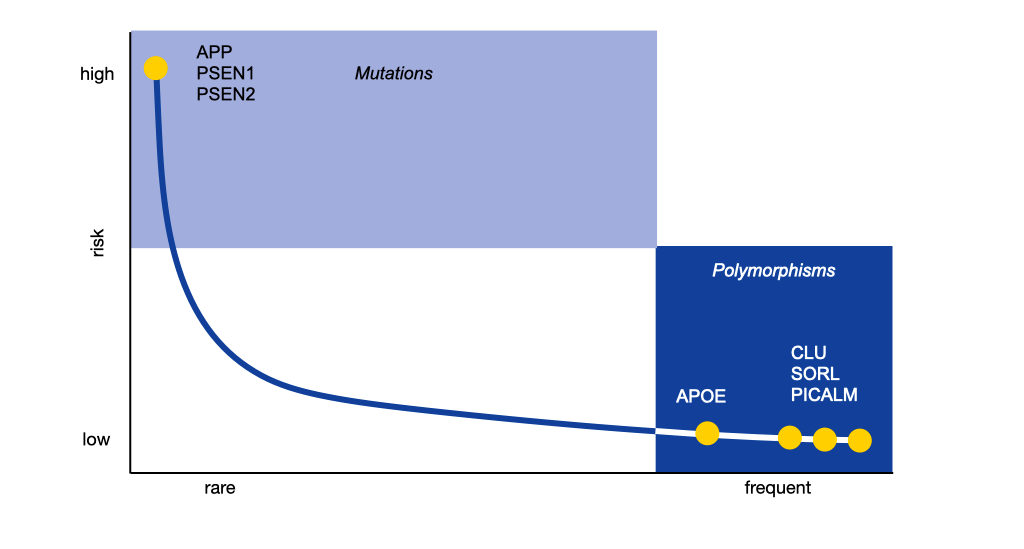

Genetic factors involved in Alzheimer’s disease

Left: Mutations at three sites in the human genetic material cause familial Alzheimer’s disease (Amyloid precursor protein, APP, Presenilin 1, PSEN1; Presenilin 2, PSEN 2). They account for less than 1 % of all cases of Alzheimer’s disease. All known mutations increase the production of beta-amyloid in the brain. Right: Several genetic risk factors have been identified which do not cause the disease but increase the individual susceptibility. The respective genes are related to lipid metabolism, immune regulation and intracellular transport mechanisms. The strongest of these risk factors is the ε3 variant of the gene for Apolipoprotein E (APOE).

Treatment decisions and care planning

At the end of the comprehensive evaluation decisions must be taken on the diagnosis and on appropriate non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments. Ideally, a discussion including the professionals involved as well as the person with dementia and the principal carer should be held to assess the needs, plans and resources of the individual and their family with the aim of establishing an individualised person-centred care plan.

Read more about the care plan in CONNECT section “Planned and proactive management”.