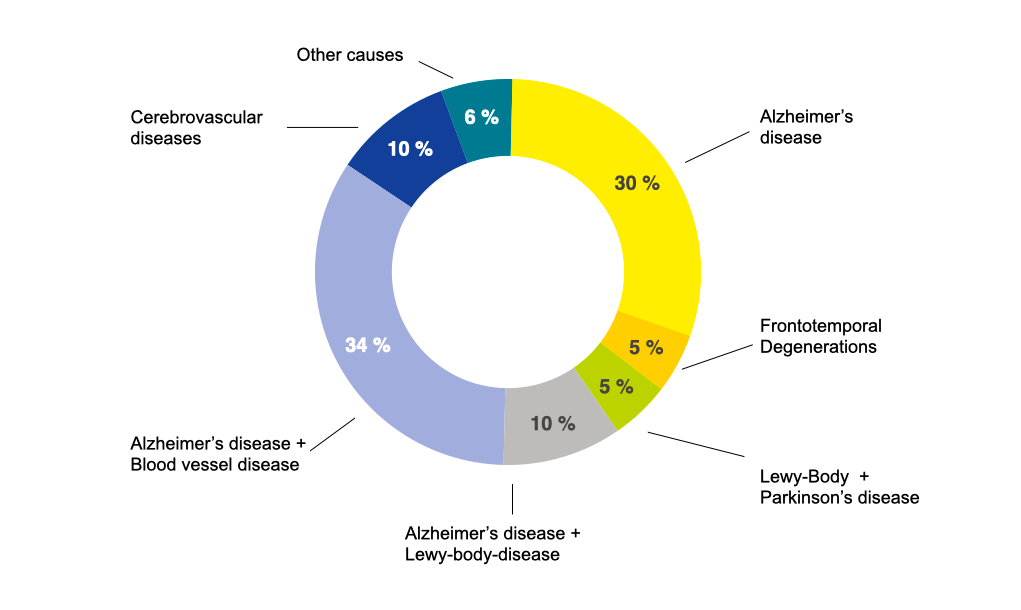

Dementia is not a disease but a condition that can be caused by various diseases. Most commonly, it is a result of a brain disease where nerve cells gradually disappear due to neurodegenerative processes or where energy supply fails due to diseases of blood vessels within the brain.

Neurodegenerative diseases

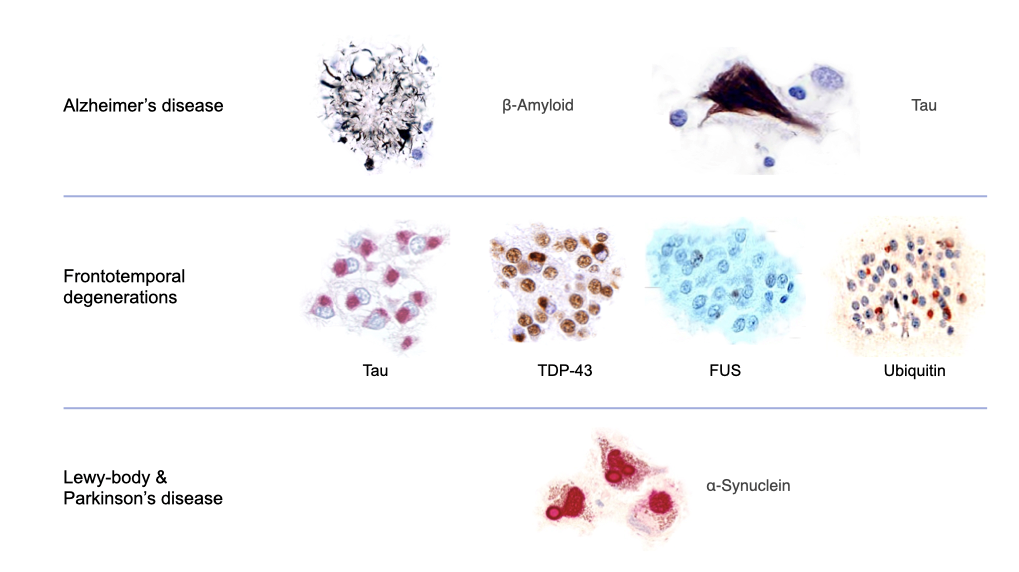

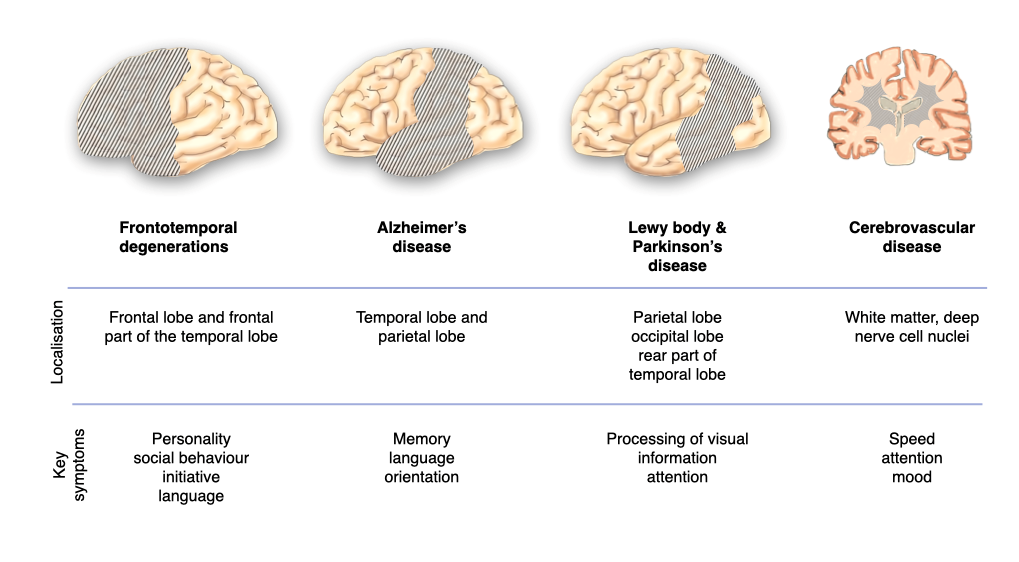

The most frequent causes of dementia are neurodegenerative diseases where nerve cells are gradually lost. Among the neurodegenerative diseases, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common, followed by frontotemporal degenerations, and Lewy body diseases (which include Parkinson’s disease). In the neurodegenerative diseases, errors in the processing of nerve cell proteins lead to the accumulation and deposition of the modified proteins within and outside of nerve cells, which has a negative impact on nerve cell functioning and viability.

The most frequent causes of dementia

Alzheimer’s disease is characterised by two protein abnormalities as well as dysfunctionand loss of nerve cells predominantly in the temporal and parietal lobes. The protein abnormalities include

- patchy precipitation of β-amyloid outside of nerve cells. This is reflected in β-amyloid deposits on positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and lower than normal β-amyloid concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid (accessible through lumbar puncture);

- accumulation of tau within nerve cells which also can be visualised by PET imaging and results in elevated tau concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid. Both protein changes are not specific for Alzheimer´s disease, as they also occur in other brain diseases, e. g. in Lewy body disease and frontotemporal degenerations. The dysfunction of nerve cells can be shown by reduced glucose consumption in typical locations on PET imaging. The loss of nerve cells leads to shrinkage of certain parts of the brain, particularly of the hippocampus. The reduced size of the hippocampus can be demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

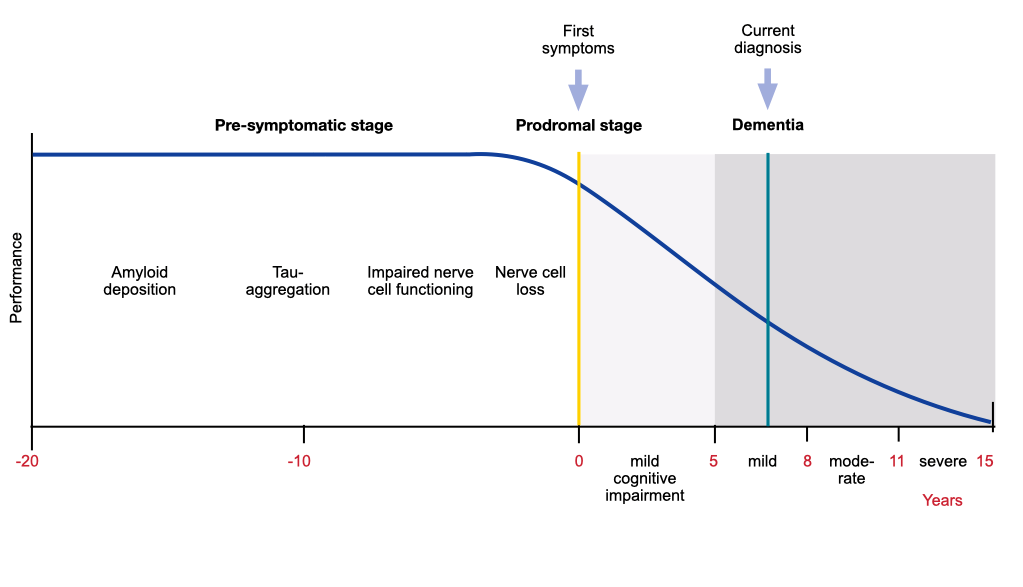

The neurodegenerative process of Alzheimer’s disease begins many years before the onset of symptoms. β-amyloid deposition comes first, followed by tau aggregation into neurofibrillary tangles, reduced glucose metabolism and impairment of episodic memory.

Evolution of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the brain

Frontotemporal degenerations are a clinically and pathologically heterogeneous group characterised by relatively selective, progressive atrophy involving the frontal or temporal lobes or both. Several protein abnormalities have been implicated in frontotemporal degeneration, including cellular inclusions containing predominantly phosphorylated tau.

Lewy body diseases (including Parkinson’s disease) are marked by the formation within nerve cells of Lewy bodies from a normal protein called alpha-synuclein, involving mostly the parietal and occipital lobe.

The origins of these processes (e.g., genetic predisposition, defective clearance mechanisms) are only partly known.

Deposition of proteins in the neurodegenerations

Images adopted from Cairns et al. (2007) and Mackenzie et al. (2007)

Cerebrovascular diseases

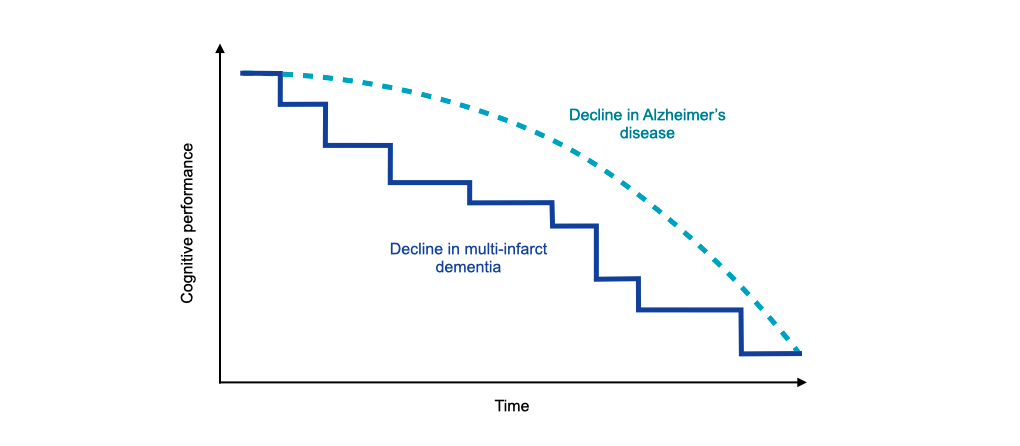

The second most frequent cause of dementia are diseases affecting the blood vessels in the brain (cerebrovascular diseases), which supply nerve cells with blood, oxygen and nutrients. Deposition of materials in blood vessel walls or blood clots (thrombi) reduce or abolish the energy supply of nerve cells and nerve cell connections. Alzheimer’s disease and small vessel changes often coexist, particularly in older people.

There are several forms of cerebrovascular dementia. Dementia can be caused by:

- Changes in small blood vessels within the brain: This is the most frequent form of cerebrovascular dementia. Narrowing of small blood vessels results in a gradual loss of abilities.

- Multiple small infarcts which become clinically manifest as a series of strokes: This form of cerebrovascular dementia is called “multi-infarct dementia”. It is characterised by a stepwise deterioration of cognitive abilities.

- Single brain infarcts in strategic locations: They are caused by a sudden interruption of blood supply in strategically important places of the brain, e. g. in the thalamus. The clinical expression of a brain infarct is a stroke.

- Bleedings within the brain and chronic lack of blood perfusion.

Stepwise progression of multi-infarct dementia

Potentially reversible causes of dementia

Unfortunately, only very few causes of dementia (less than 2 %) are potentially remediable so that dementia may revert to normal. These rare causes include normal pressure hydrocephalus, dysfunction of the thyroid or parathyroid glands, excessive use of alcohol, vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, and depression.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus: The liquid spaces in the centre of the brain (ventricles) are enlarged although the liquid pressure is normal or only slightly elevated (hence the name). It is assumed that increased pulsation of the cerebrospinal fluid leads to gradual expansion of the ventricles, which compresses the adjacent brain tissue and causes neurological and psychiatric symptoms. The classic symptom triad includes urinary incontinence, gait disorder and dementia.

Dysfunction of the thyroid or parathyroid glands: Deficiency of thyroid hormone slows down all metabolic processes of the body and leads to weakness, fatigue, poor concentration and memory, reduced mental speed, hearing difficulty, loss of initiative, and depression. Increased activity of the parathyroid glands results in demineralisation of bones with deformations and fractures, calcification of other tissues (e.g. kidney stones), cognitive disorders, loss of initiative and depression.

Excessive alcohol consumption: Excessive and chronic use of alcohol has numerous detrimental effects on the brain and increases the risk for dementia. The biological mechanisms are not fully known. Certainly, exaggerated alcohol consumption is associated with other factors that increase the risk of dementia such as unbalanced diet, vitamin deficiency and elevated blood pressure. Alcohol-related dementia is characterised by memory disorder but also by frontal lobe symptoms including loss of initiative and impairment of executive functions.

Vitamin B12 or folate deficiency: Lack of vitamin B12 or folic acid leads to anemia, disorder of nerve conduction (neuropathy), unsteady gait, confusion, depression and cognitive impairment involving memory and executive functions.

Depression: Depression is a strong risk factor for dementia, but the reason is not clear. Possible explanations of the association include cerebrovascular changes, excessive release of adrenal gland hormones (glucocorticoids) resulting in shrinkage of the hippocampus, increased deposition of beta amyloid, inflammatory changes and deficiency of nerve growth factor.

Localisation determines the clinical picture

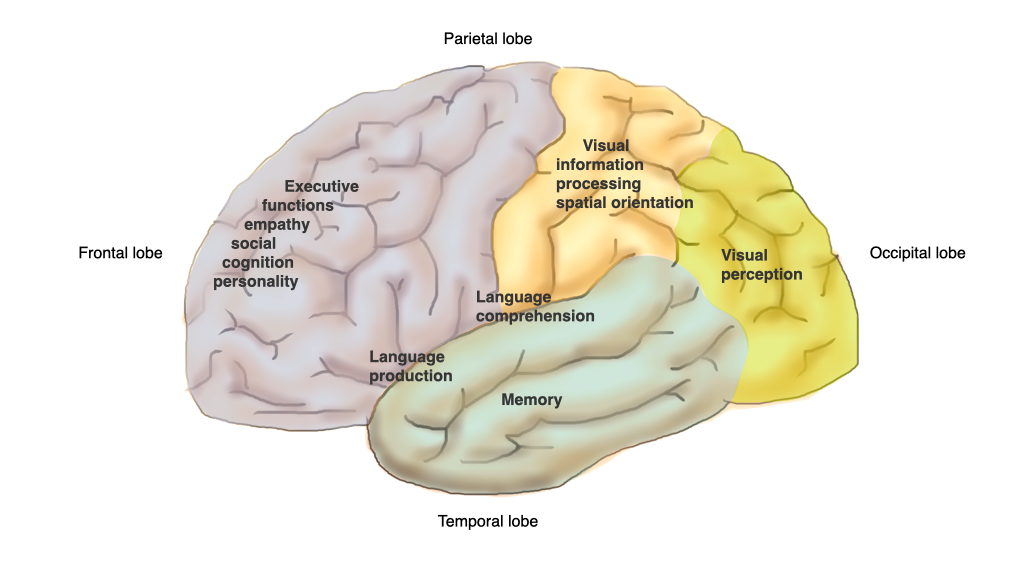

Different parts of the brain are involved in different functions.

Regions of the brain mantle

Localisation of major brain functions

Therefore, the symptoms of dementia depend on the localization of the underlying brain disease. A specific localization in a certain part of the brain results in a specific clinical manifestation of dementia.

Localisation determines the clinical picture

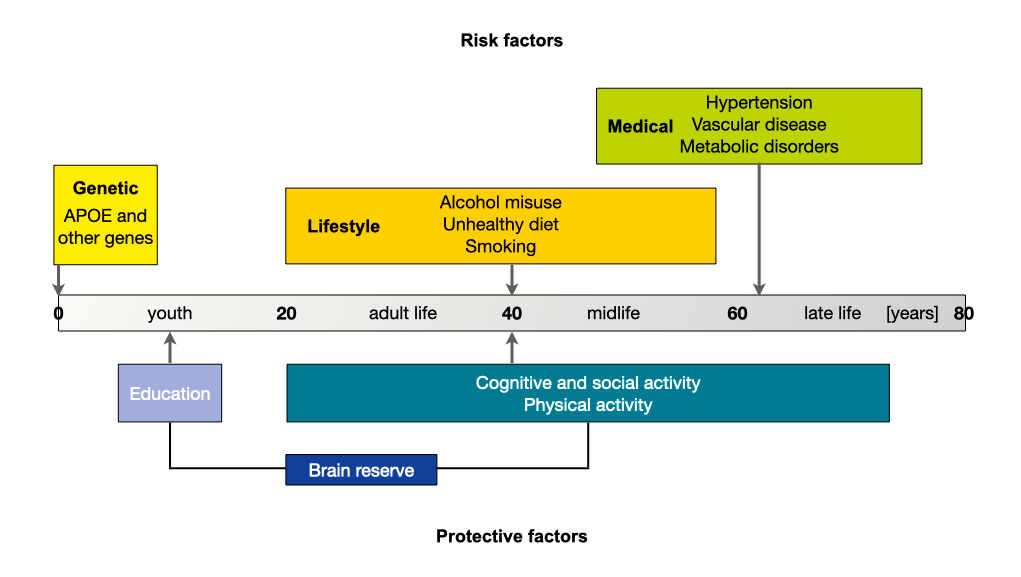

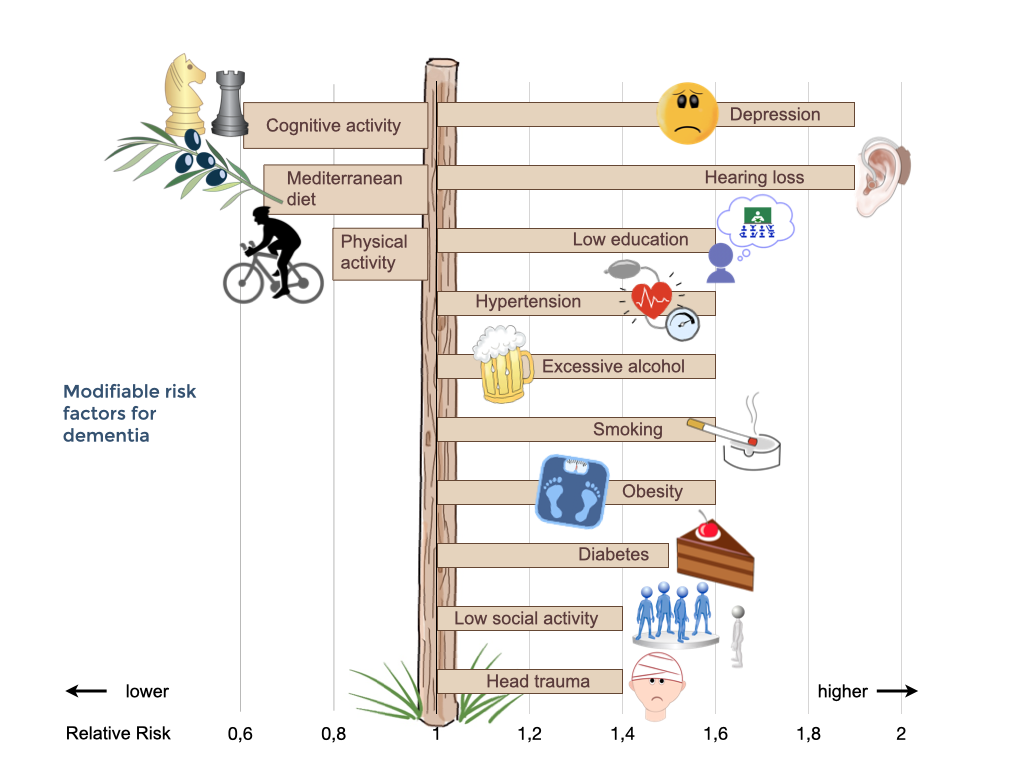

Risk factors for developing diseases causing dementia

There are several risk factors that influence the likelihood of developing dementia. Some cannot be changed, for example age or genetic factors including very rare mutations with strong influence and frequent variants (polymorphisms) such as APOE4 with weaker influence. About 25% of people aged 55 years and older have a family history of dementia. The risk of developing dementia for members of these families is approximately 20%, as compared with 10% in the general population. However, many other factors that are associated with an increased risk of acquiring dementia can be modified. These include diabetes, midlife hypertension, midlife obesity, physical inactivity, depression, smoking, and low educational attainment. Luckily, there are also several protective factors which lower the risk of dementia.

Risk factors and protective factors

Modifiable risk factors for dementia

Co-morbid conditions

Since most people with dementia are older, they are very likely to have multiple, often chronic, health conditions in addition to dementia. These must be adequately addressed in order to minimise cognitive and functional impairment, prevent or mitigate behavioural symptoms, and optimise quality of life. The presence of dementia may complicate the management of other conditions and undermine a person’s ability to live with health conditions.

Some physical problems occur more often in people with dementia than older adults without cognitive impairment, e.g. falls, delirium (acute confusional state), epileptic seizures weight loss, malnutrition, type-2-diabetes, incontinence, sleep disorder, dental problems, impaired sexual function and frailty. About 25 % of people with dementia have a clinically relevant depression.