What does the diagnosis of dementia mean?

For healthcare professionals, the diagnosis of dementia means to identify an abnormal health condition – usually a brain chronic brain disease – that explains the person’s symptoms and signs. The diagnosis is a prerequisite, justification and guideline for treatment and care, and it entitles people to financial recompensation. For the person, the diagnosis of dementia is a verdict about their present and future which may profoundly change not only their own lives but also the lives of their family. Therefore, the diagnosis of dementia requires high professional skills, comprehensive and accurate assessments as well as caution and watchfulness. It must be communicated with compassion and always linked to the available treatment options.

From the perspective of the person with dementia and their family the diagnosis of dementia is life-changing event

How do people with dementia feel about diagnosis?

From the perspective of people with dementia, the diagnosis is both a burden and a relief. It imparts the sad truth of a severe progressive brain disease that presently can be slowed down but not cured. On the other hand, the diagnosis is a transition from uncertainty, apprehension and worry to treatment and support. Dealing with the diagnosis of dementia is a complex and lengthy process that needs time. Most people with dementia and most carers prefer that the diagnosis be disclosed to them. Major reasons for this are the opportunity to plan, receive treatment, obtain information, and acquire coping strategies. However, in reality only about half of the people with dementia are being diagnosed.

Why is the diagnosis important?

An early and correct diagnosis of dementia is important for several reasons. The diagnosis provides an explanation for signs and observations that may have been worrying or distressing a person or their family. It is often coming as a relief to learn that changes in cognition, daily activities, behaviour or personality are symptoms of a disease.

Some causes of dementia are partly or completely reversible if identified early and treated adequately (e.g. vitamin or hormone deficits, normal pressure hydrocephalus, bleedings within the head). A number of other medical conditions that worsen dementia or accelerate its course (e.g. depression, elevated blood pressure, diabetes, abnormalities of lipid metabolism, heart diseases) can be effectively treated.

Most importantly, the diagnosis is a prerequisite and guidance for all treatment and care interventions, and for establishing an individual care plan. Therefore, the diagnosis needs to be comprehensive and must go beyond the assessment of symptoms by including individual needs, preferences, risks, resources and available support. Timely diagnosis provides time for people with dementia and their families to prepare for the future and plan ahead.

Another role of the diagnosis is to enable access to social and financial benefits (e. g. from health or social insurance, disabled pass) and to counselling and support. Even if support is not currently needed, it is important to know what kind of help is available.

Who makes the diagnosis?

Usually, general physicians (GPs) are the first point of contact for people with suspected dementia. Using brief tests and questionnaires they can perform an initial assessment of cognitive abilities, activities of daily living and behaviour. GPs are also in a good position to identify or rule out physical causes or contributing factors of dementia. Specialists (neurologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, geriatricians) apply more sophisticated diagnostic instruments and technologies (neuropsychiatric tests, CSF analyses, brain imaging) to detect prodromal and mild stages of dementia and distinguish between causes of dementia. Specialists are also important to review the diagnosis upon follow up.

Since dementia impacts on all aspects of life, other professional groups can contribute to the diagnosis by providing valuable information, e. g. nurses, social workers, occupational therapists and physical therapists.

All professional groups can contribute to diagnosis

The contribution of non-medical professions to the diagnosis of dementia

| Nurses | Social workers | Occupational therapists |

| • Careful and long-term observation of the person’s performance and behaviour • Execution of assessments • Initial counseling of people with dementia and carers about diagnosis | • Assessment of cognitive abilities in daily life, e. g. understanding information, decision making, communicating • Impact of symptoms on daily activities or work • Assessment of a person’s care and support needs • Referral to community services | • Assessment of individual strengths and limitations • Evaluation of home environment including safety risks • Need for environmental modification • Individual goal setting • Implementation of assistive technology |

How does the diagnosis of dementia proceed?

The diagnosis of dementia usually does not start in the physician’s office. Often, family members, friends, or colleagues at work notice something amiss about the person before the person does so. This may happen long before the person seeks medical attention. Therefore, raising public awareness about dementia and destigmatisation are essential for timely diagnosis. The diagnostic process can be divided into four steps:

Step one: Someone needs to recognise changes of cognitive abilities, functional performance, behaviour or personality. This may be the individual or family members, friends or colleagues at work.

Step two: Verifying the changes using interviews and cognitive tests.

Step three: Identifying the cause(s) using physical examination, laboratory work-up, cerebrospinal fluid examination (lumbar puncture), brain imaging, in selected cases genetic testing.

Step four: Finding points of intervention in terms of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment, support and environmental modification – taking into consideration the person’s needs, preferences, resources and support.

The process of diagnosis, Step 1: Detecting changes of cognition, daily activities and / or behaviour

| Domain | Example |

| Cognition | Memory: Repetitive questioning on conversations, misplacing personal belongings, forgetting events or appointments, getting lost on a familiar route Executive functions: Poor judgment, inadequate understanding of safety risks, poor decision-making ability, difficulty planning and carrying out complex or multi-step activities Visuo-spatial abilities: Inability to recognise faces or common objects, difficulty finding objects in direct view despite good visual acuity, inability to align clothing and body Language: Difficulty finding the correct words while speaking, hesitant speech, grammatical and syntactical errors, disfigured handwriting, poor language comprehension |

| Daily activities | Newly occurring and persistent difficulty organising the household, managing finances, using public transportation, using computer and mobile phone, operating domestic appliances, buying correct items |

| Behaviour and personality | Mood swings uncommon for the person, agitation, apathy, inertia, social withdrawal, loss of interest in hobbies, loss of warmth and empathy, disinhibition, aggressiveness, obsessions or compulsions, repetitive and stereotyped behaviour, socially unacceptable behaviours |

The process of diagnosis, Step 2: Verifying the changes using tests and interviews

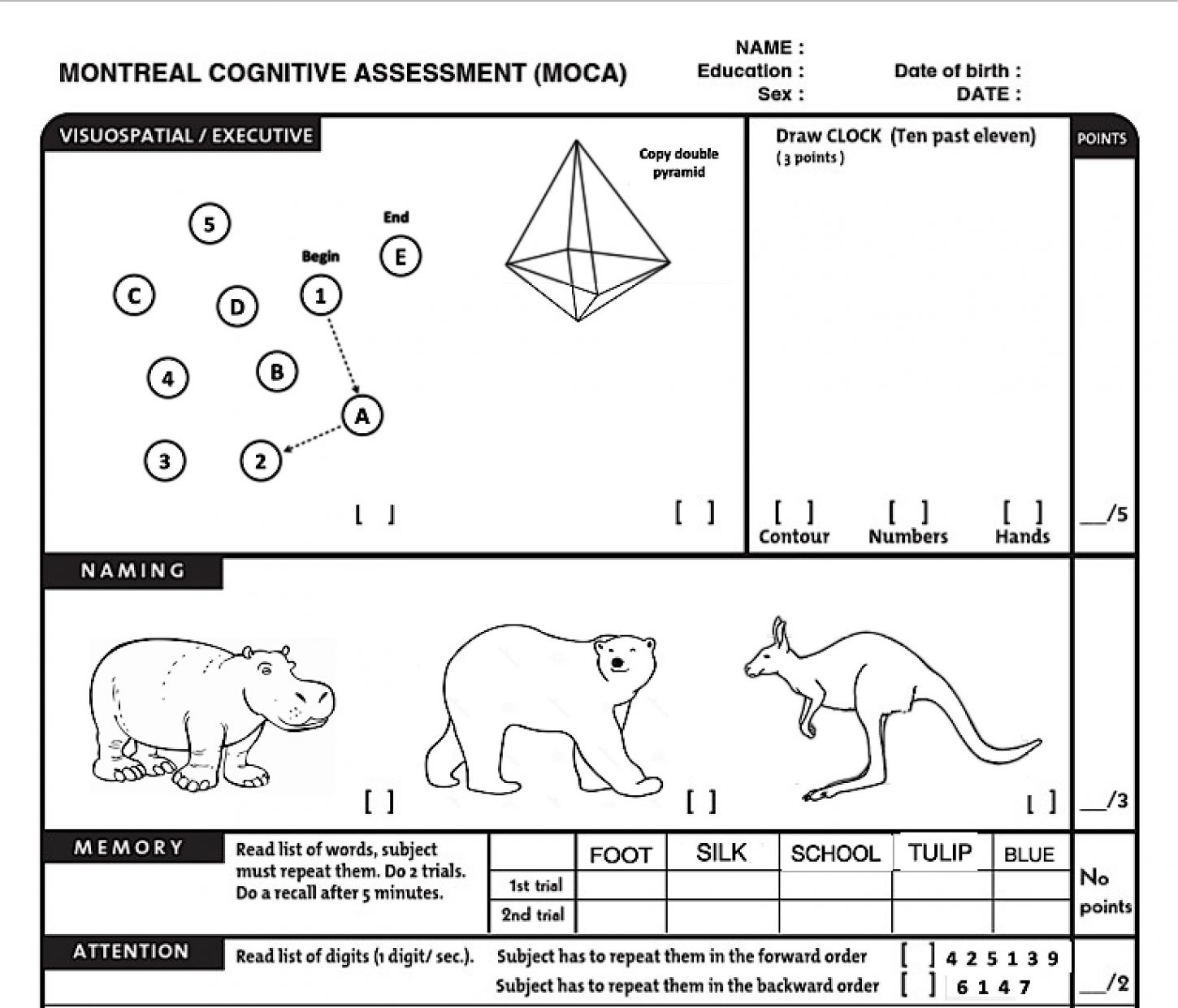

Cognitive testing is needed to objectively assess the degree and pattern of cognitive impairment. At the level of primary care, a brief mental status examination should be carried out. However, it may not be sufficient to provide a reliable diagnosis. At the level of secondary care, comprehensive neuropsychological testing by a (neuro)psychologist is often helpful. For the assessment of the various cognitive domains valid and reliable instruments are available.

Neuropsychological testing

Cognitive testing should provide evidence of a lower performance in one or more cognitive domains that would be expected for the person’s age, gender and educational background. Upon repeated measurement a decline of test performance should be evident.

| Type of test | Comments |

| Brief mental status tests | • May be used at the level of primary care (general practitioners) • Can be administered by trained nurses • Provide an overall assessment of cognitive ability • Cut-off values for the decision between normal and abnormal are available • Not appropriate to evaluate specific cognitive functions • Most instruments are not sensitive for mild degrees of impairment |

| Neuropsychological tests and batteries | • For use at the level of secondary care • Should be administered and interpreted by (neuro)psychologists • May take up to one hour to complete • Provide information on specific cognitive functions, e.g. memory • Compare the individual performance with age-, gender-, and education-specific norms • May enable performance profiles for the differentiation of dementia causes • Can be sensitive for mild degrees of impairment |

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA, a section is shown) is a brief but sensitive test of cognitive ability. It assesses visuospatial and executive functions, memory, attention, language, abstract thinking and orientation. The illustration above gives an impression how the MoCA looks like. It is neither the real nor the complete test. Activities of daily living and changes of behaviour can be evaluated using standardised observational scales and caregiver interviews.

| Topic of inteview | Comments |

| Onset and course of symptoms | • Dementia typically has an insidious onset over months to years • Worsening of cognition should be documented by direct observation of the person or by informant report |

| Impact on activities of daily living | • Performance on activities of daily living should be inquired from the person and a knowledgeable informant. This is important to determine whether cognitive impairment interferes with work or usual daily activities, and for assessing the severity of dementia. A decline of functional ability from a previous level should also be assessed |

| Types and pattern of symptoms | • Evaluating the course and pattern of symptoms is also important to distinguish dementia from other conditions such as depression or delirium which require immediate action |

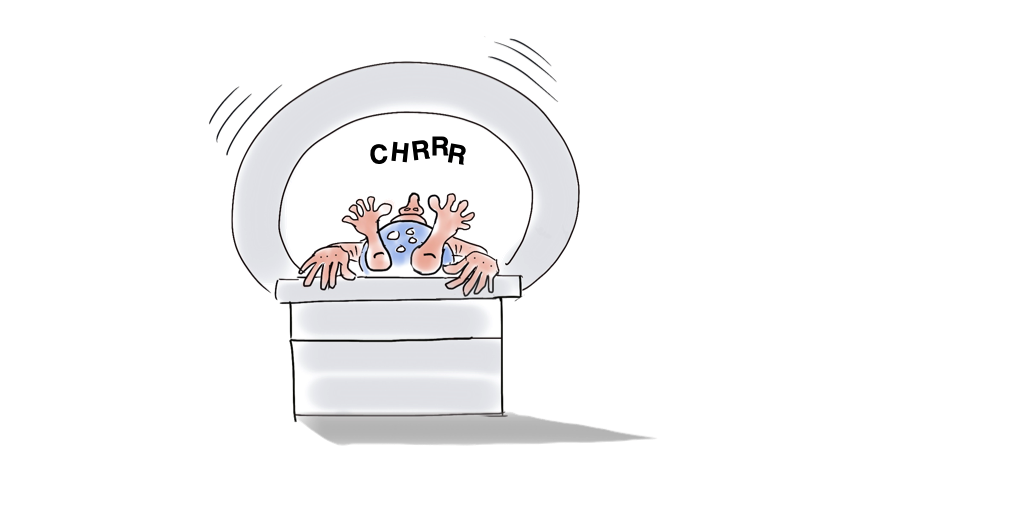

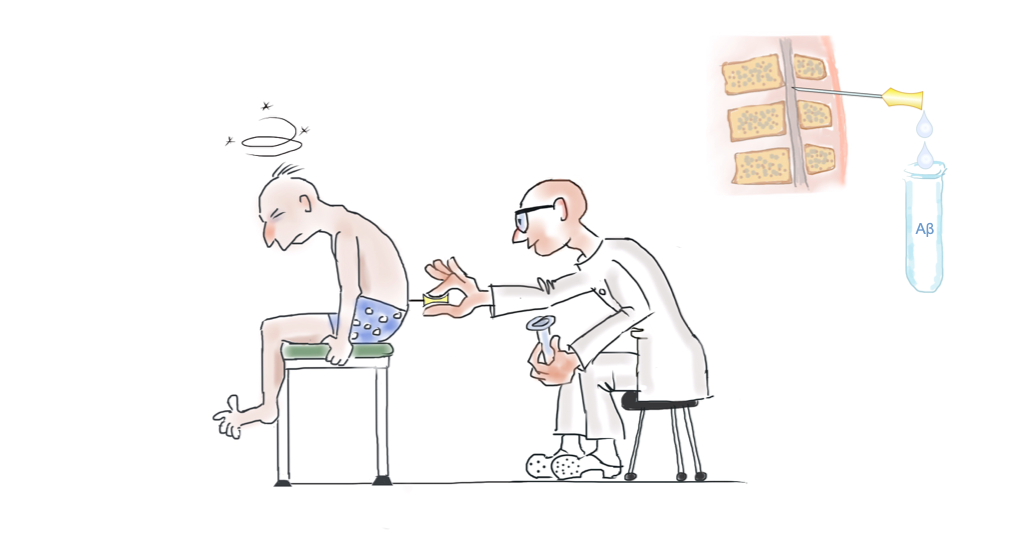

Once the deterioration of cognitive abilities, everyday functioning and / or behaviour has been determined, the underlying cause or causes need to be identified. Sometimes, the history and the pattern of impaired and preserved cognitive domains provide cues. The physical examination gives information on neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease or stroke and is useful to detect physical factors that impair cognition such as hearing loss or poor eyesight. Routine laboratory assessments are needed to show or exclude metabolic diseases (e.g. diabetes), infections (e.g. Borreliosis) and vitamin or hormone deficiencies. In the cerebrospinal fluid the concentrations of certain brain-derived proteins can be measured (particularly beta amyloid and tau). They are used to identify Alzheimer’s disease and differentiate it from other neurodegenerations. There are several modalities of brain imaging including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET). These techniques demonstrate structural changes of the brain, abnormalities of blood vessels, the regional level of activity of nerve cells, and recently also the deposition of the two proteins in the brain. Genetic tests are used in rare cases where dementia runs in families to identify heritable genetic errors (mutations).

The process of diagnosis, Step 3: Identifying the cause(s)

| Setting | Methods | May reveal |

|---|---|---|

| Primary care (general practitioner) | • Physical examination • Electrocardiogram, • Chest X-ray • Laboratory work-up • Medications list • Drug history | • Stroke, Parkinson’s disease • Heart and lung diseases • Infectious diseases, vitamin or hormone deficiency • Drug-drug interactions, adverse drug effects, polypharmacy • Drug or alcohol misuse |

| Secondary care (neurologists, psychiatrists, geriatricians, memory clinics) | • Brain imaging • Cerebrospinal fluid examination • Genetic testing | • Brain tumours, intracranial bleeding, brain atrophy • Nervous system infection, markers of neurodegeneration • Rare genetic mutations, genetic risk factors (e.g. ApoE4) |

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Cerebrospinal fluid examination (lumbar puncture)

Laboratory work-up

The final step of the diagnostic process is to identify modifiable individual circumstances that can be targeted by pharmacological, non-pharmacological or environmental interventions as part of the individual treatment plan. The goal is to maximise the quality of life for the person with dementia, to minimise risks, prevent crises and strengthen the caring network.

The process of diagnosis, Step 4: Finding individual points of intervention

| Category | Example |

| Individual needs | • Insufficient levels of activity and participation • Boredom • Loneliness, isolation |

| Risks | • Poor care and support network • Living alone • Behavioural problems • Driving |

| Environmental features | • Home hazards • Mobility barriers |

| Interpersonal issues | • Poor caregiver skills • Family conflict • Inappropriate communication style • Children involved |